It is generally believed that the art of Karate-Do can be traced back to sixth century China. There, in the Mt. Sung Hennan Province, Dharma, and the founder of Zen, a sect of Buddhism composed a sutra or collection of precepts to promote the physical development of the monks and missionaries to help protect them from bandits and criminals.

It is generally believed that the art of Karate-Do can be traced back to sixth century China. There, in the Mt. Sung Hennan Province, Dharma, and the founder of Zen, a sect of Buddhism composed a sutra or collection of precepts to promote the physical development of the monks and missionaries to help protect them from bandits and criminals.

The sutra developed by Dharma was called “Ekkin-Kyo,” and it is believed that it evolved into Shaolin Temple Kenpo, ” the way of Fists”. Unfortunately, not much is known about this period in the history of Karate-Do and the relationship between Karate-Do and Shaolin Kenpo remains an ambiguous one.

In the ancient times there was no law prohibiting people from arming themselves. Weapons were standard in fighting, and most cultures have their own sword fighting system. Japan is renowned for its Samurai culture in the caste feudal system. The code of the Samurai was developed in the 18th century. The effective use of a sword was essential for a warrior. Samurai practiced with them and carried them in daily life as the symbol of their class.

In the later part of the 14th century however, the influence of the Chinese techniques on the development of Karate-Do becomes much more apparent. Under the ruler King Hassi of Chuzan of Okinawa, a policy was enacted prohibiting the people of Okinawa from arming themselves. In the 16th century, Japan’s most southern clan, the powerful Satsuma clan, invaded Okinawa. They colonized Okinawa for use as a trading post with China. They also levied taxes on their goods. These events forced the people of Okinawa to secretly develop the so-called ” Te”. In addition to the weaponless fighting methods, Okinawans were using their farm tools for defense and developing fighting systems. These systems were referred to as “Te”, meaning hands, techniques, and methods. In combination with the influence of Chinese techniques it was often called “Kara”, referring to the Tang Dynasty of China, that there was a sense of more preciousness as today’s foreign goods, and “Te”, techniques.

In 1868, the Meiji restoration ended the Japanese feudal system. Japan opened free trade with western countries. Western culture, its industrial methods and educational system flourished in Japan in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. This Meiji restoration brought the influence of western laws and values to Japan. The major reform was the abolition of the Samurai feudal system and the establishment of a centralized governing system. In short time, the new laws and customs were used to abolish the traditional carrying of the samurai sword. Hairstyles were also changed to a westernized cut. The Japanese no longer wore Samurai knots in their hair, and they were encouraged to wear western suit and dress.

In this era, in Karate, there were no specific styles, names, ranks or belts that are known today. Lacking formal names, people generally referred to various labels by putting the names of masters and Katas (as instructional methods) together, creating a label for the particular school. Similarly, distinctions of Karate were also named according to their distinct districts.

The three prominent centers of Karate in Okinawa were Shuri, Naha, and Tomari. You must understand that the teaching methods at the time were not like today’s systematic rational methods. There were only a few Katas in each location, which were taught and developed. Only a small number of people took the private lessons. Later, Karate came to Tokyo, the capital of Japan, which recorded an exhibition in 1922 of Gichin Funakoshi. Funakoshi’s Karate-Do later became the modern Shotokan system.

In this era many prominent Karate masters came to Japan, even though Okinawa was a part of Japan, Okinawa’s history and its remote location resulted in the people of Okinawa being considered as colonized peasants and mistreated by most common Japanese. The most prominent Karate Masters came to Japan, among them were; Kenwa Mabuni, founder of Shito Ryu, and Chojun Miyagi, founder of Goju Ryu.

After the Karate Masters came to Japan in the 1920’s, the present day style of karate developed; they have descended from the primitive Okinawan forms. It was not until the 1930’s that a label was claimed and developed as a style, forced by the other established Japanese martial arts societies. Chojun Miyagi, a senior disciple of Kanryo Higaonna, first claimed a label to his style as Goju-Ryu (Hard Soft Style). Kenwa Mabuni named his style as Shito-Ryu. These two were very close friends and developed most of the technical bases of today’s Karate.

The form of Kumite as practiced in today’s Karate, was also influenced by other Japanese martial arts such as Jujitsu, Judo and Kendo masters. Until the late 1930’s, Karate-Do practice emphasized only the Kata and its applications.

The term Karate-Do also was influenced by the Japanese Zen Buddhist sect and became “Kara” (empty) “Te” (techniques) and “Do” (The way of.). Dr. Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, established the current belt system during this era. Judo was a synthesis of Daito-Ryu and other Ju Jitsu. Dr. Kano established and created Ju (Soft) Do (The way of) from Jujitsu; these were methods for the development of ideology not just the development of technical skills.

Gichin Funakoshi aimed to teach only university students who were candidates for the governing leadership group. Funakoshi did not like his students to participate in tournaments.

That young Japanese group developed today’s sparring methods and later developed the basis of today’s tournament systems, not those of Okinawan residents’ Karate instructors. Okinawan masters never even dreamed of competing with each other under established rules. They thought Karate techniques were so deadly that it would be impossible to hold any tournament. The first appearance of the modern version of a Karate tournament was held in the late 1950’s in Japan. All Japan Collegiate Karate tournaments were the first tournaments ever held in Japan including Okinawa. It went on to develop Karate-Do worldwide.

“Tode” Sakugawa (1733-1815)

The mysterious Koshokun of a Chinese envoy settled in Okinawa for some time. His most famous student was Satunuku “Tode” Sakugawa (1733-1815). It is believed Sakugawa became a student of Koshokun in 1756. Sakugawa was a student of Takahara Peichin (1683-1760) (Peichin is a title of status) until the arrival of Koshokun in Okinawa. At that time Sakugawa was granted permission from Takahara Peichin to train under Koshokun.

Sakagawa traveled to China with Koshokun to study Kempo. He returned to Okinawa in 1762 to introduce this fighting method. Before long Sakugawa was considered an expert in the Chinese hand fighting method. It is said that Sakugawa was awarded the title of Satonushi for his services to the Okinawa King.

Sakugawa soon started to teach the Chinese hand in Okinawa. Combining what both his teachers had taught him, he structured a training system. This made him the first Okinawan teacher of Tode. Many of his students rose to greatness. Among them were Chokun Satunku Makabe, Satunuku Ukuda, Ch. Matsumoto, Kojo, Yamaguchi (“Bushi” Sakumoto), Unsume, and Sokon ”Bushi” Matsumura.

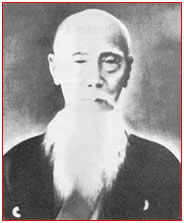

Sokon ‘Bushi’ Matsumura (1797-1889)

Sokon ‘Bushi’ Matsumura (1797-1889)

Contrary to some claims, Bushi Matsumura was born in 1797, and died in 1889. Supposedly, some have found new evidence that would seem to indicate that Bushi Matsumura was born in 1809. But this is not the case, because we know he died when he was 92. According to some sources, Bushi’s family name was Kiyo. Matsumura grew up in Yamagawa village of the city of Shuri, Okinawa. He was partly Chinese. Sakugawa trained Bushi at Akata when he was 14, in 1810. According to tradition, it was at Bushi’s father’s request that Sakugawa teach him. Some say that to train Bushi to block, Sakugawa tied to him to a tree so he could not move. Then he threw punches at him. Kise’s page says, “He was recruited into the service of the Sho family and was given the title Satunuki, later rising to Chikutoshi…” This is probably the reason he had the title of Chikudon. Upon his recruitment, the Sho Ko, the king of Okinawa at the time, desired to have him change his last name, as was the custom, and suggested the name Muramatsu, or “village pine.” Sokon requested of the king to let him change the name to Matsumura, or “pine village.” So the king granted this to him. Sakugawa trained him until his death, and then Sokon was probably on his own for a while. According to oral history, he studied “Tode” Sakugawa for 4 years.

Matsumura married a woman by the name of Yonamine Chiru, who came from a family known for their martial arts skills. According to tradition, this was when he was 19 years old, which would make it 1815. Yonamine said she would never marry a man that could not beat her. The story goes that he faught her and won, and that is the reason she married him (of course she must have loved him too). There are many funny stories that have circulated about these two.

The karate of Shuri was further developed by Bushi Matsumura . Today there are many different styles descended from the original Matsumura style of Shorin-Ryu. The Orthodox style of Hohan Soken was the only style taught to the public that has stayed the most like the original Matsumura Shorin-Ryu, contrary to some claims.

Stories about Matsumura

There are two very popular and often-told stories that demonstrate Matsumura’s strategy of defeating the enemy before you even fight him by intimidation and demoralization. The first story is when Matsumura fought a bull. Sho Tai had gotten this bull from the Emperor of Japan. The king decided to put Matsumura against the bull. Matsumura wasted no time, and went to see the bull-keeper. He asked to see the bull. So the keeper took him to it. He was dressed in his armor. He tormented the bull day after day until it feared him and knew well who he was. Finally the day came for Matsumura to fight the bull. They let the bull out into the arena, and then Matsumura went out to fight it. The bull was terrified and ran away. The story goes that because of this, the king give him the title of Bushi.

And then there is the old story about the eyes of Matsumura. A pipe craftsman and martial artist challenged Matsumura to a fight. This man told Matsumura to meet him at a certain spot at a certain hour early in the morning. He decided that he would show up very early to examine the terrain and come up with a strategy to gain an advantage. To his surprise, Matsumura was already there waiting. Matsumura had already out-thought his opponent. So when they got ready to fight, he caught sight of Matsumura’s eyes, which had the “look of death” in them. The man was immediately struck with fear, and his courage was destroyed. He just fell to the ground and began to cry. Matsumura told him that his only thought was to win, and that had defeated him. Matsumura’s attitude was that of the Samurai. It was the “resolute acceptance of death” as spoken of by Musashi.

Another person Matsumura had an interchange of martial knowledge with was a man named Chinto, a pirate from Southern China (according to some, he was not a pirate at all, but a trader, and he did not plunder). He drifted ashore to Okinawa. Something must have happened to his ship. When he got there, he began to loot and plunder because of hunger. The king received word of this, and sent Bushi to hunt him down and stop him. So when Bushi found him, they fought each other but were matched. Some say that it was because Chinto was very expert at change-body just like Matsumura. When all attempts to apprehend the pirate failed, strangely enough, Bushi befriended him and exchanged martial knowledge with him. Thus we have the kata named Chinto with the techniques in it that Bushi got from him. It is a mystery as to what Chinese system these techniques are from.

Bushi Matsumura studied under a Chinese master for a time by the name of Channan (Chiag Nan) who was a diplomat sent to Shuri from China. Bushi created two kata from what he had learned that were known as Channan Sho and Dai. Later, the names were changed to Pinan (Ping An) Shodan and Nidan. In the Matsumura system, these two are considered the basic, or “kihon” kata.

It is said by some that a Chinese master by the name of Ason taught a Chinese kata by the name of Naifanchin in the area of Naha. Some say that the kata was taught in Naha-te for a while (but is no longer had in Naha-te styles.) Matsumura studied from Ason for a time. Later, Matsumura took this kata and broke it up into two parts: Naifanchin Shodan and Nidan. The origin of Naihanchi Sandan is more obscure. It is not a Matsumura kata at all, but it may have its origin in Ason’s system also.

Ankoh Itosu (1830-1916)

Born in Shuri, Okinawa, Itosu trained under karate greats Sokon “Bushi”Matsumura and Kosaku Matsumora. His good friend Yasutsune Azato recommended him to the position of secretary to the king of the Ryukyu Islands. He was famous for the superior strength of his arms, legs and hands. Itosu was said to have even walked in the horse stance (from which he received his nickname, Anko). Itosu supposedly was easily able to defeat Azato in arm wrestling. Itosu had very strong hands and could crush a thick stalk of bamboo with his vice-like grip. It is said that he walked past the imperial tombs everyday and would practice his punches against the stone walls that lined the road. Itosu believed that the body should be trained to withstand the hardest of blows. In the tradition of Itosu, Pinewood Karateka train intensely to develop a powerful body and spirit.

Describing the art in his own words: “Karate means not only to develop one’s physical strength but to learn how to defend oneself. Be helpful to all people and never fight against one person. Never try to strike if possible. even when taken unawares, as perhaps meeting a robber or a deranged person. Never face others with fists and feet. As you practice karate, try to open your eyes brightly and keep your shoulders down, stiffen your body as if you are on the battleground. Imagine that you are facing the enemy when you practice the punching or blocking techniques. Soon you will find your own striking performance. Always concentrate attention around you. A man of character will avoid any quarrels and loves peace. Thus the more a karateka practices the more modest he should be with others. This is the true karateka.”

Below is a letter written by Itosu Sensei in October of 1908. This letter preceded the introduction of karate to Okinawan schools and eventually to the Japanese mainland.

Tode did not develop from the way of Buddhism or Confucianism. In the recent past Shorin-ryu and Shorei-ryu were brought over from China. They both have similar strong points, so, before there are too many changes, I should like to write these down.

1. Tode is primarily for the benefit of health. In order to protect one’s parents or one’s master, it is proper to attack a foe regardless of one’s own life. Never attack a lone adversary. If one meets a villain or a ruffian one should not use tode but simply parry and step aside.

2. The purpose of tode is to make the body hard like stones and iron; hands and feet should be used like the points of arrows, hearts should be strong and brave. If children were to practice tode from their elementary-school days, they would be well prepared for military service. When Wellington and Napoleon met they discussed the point that tomorrow’s victory will come from today’s playground’.

3. Tode cannot be learned quickly. Like a slow moving bull, that eventually walks a thousand miles, if one studies seriously every day, in three or four years one will understand what tode is about. The very shape of one’s bones will change.

Those who study as follows will discover the essence of tode:

4. In tode the hands and feet are important so they should be trained thoroughly on the makiwara. In so doing drop your shoulders, open your lungs, take hold of your strength, grip the floor with your feet and sink your intrinsic energy to your lower abdomen. Practice with each arm one or two hundred times.

5. When practicing tode stances make sure your back is straight, drop your shoulders, take your strength and put it in your legs, stand firmly and put the intrinsic energy in your lower abdomen, the top and bottom of which must be held together tightly.

6. The external techniques of tode should be practiced, one by one, many times. Because these techniques are passed on by word of mouth, take the trouble to learn the explanations and decide when and in what context it would be possible to use them. Go in, counter, release; is the rule of torite.

7. You must decide whether tode is for cultivating a healthy body or for enhancing your duty.

8. During practice you should imagine you are on the battle field. When blocking and striking make the eyes glare, drop the shoulders and harden the body. Now block the enemy’s punch and strike! Always practice with this spirit so that, when on the real battlefield, you will naturally be prepared.

9. Do not overexert yourself during practice because the intrinsic energy will rise up, your face and eyes will turn red and your body will be harmed. Be careful.

10. In the past many of those who have mastered tode have lived to an old age. This is because tode aids the development of the bones and sinews, it helps the digestive organs and is good for the circulation of the blood. Therefore, from now on, tode should become the foundation of all sports lessons from elementary schools onward. If this is put into practice there will, I think, be many men who can win against ten aggressors.

The reason for stating all this is that it is my opinion that all students at the Okinawa Prefectural Teachers’ Training College should practice tode, so that when they graduate from here they can teach the children in the schools exactly as I have taught them. Within ten years tode will spread all over Okinawa and to the Japanese mainland. This will be a great asset to our militaristic society. I hope you will carefully study the words I have written here.

Anko Itosu. Meiji 41, Year of the Monkey (October 1908).

Kanryo Higaonna (1853-1915)

Kanryo Higaonna (1853-1915)

According to late Dr. Shiro Hattori, a Japanese linguist Okinawans and Japanese share the same linguistic family lineage. They, however, apparently separated at least two thousand years ago, so the two do not sound like the same language. Both linguistic cultures adapted Chinese characters for writing both family and given name. And yet, the Okinawan pronunciation of their family names is not neccessarily same as the Japanese pronounciation.

For example, the surname can be pronounced “Higashionna” by the Japanese, thus those who have that surname in the current island now pronounce their name “Higashionna.” The prominent historian, Dr. Kanjun Higahionna, claimed his family name should be pronounced “Higashionna.” The historian, in fact, is related to Kanryo Higaonna. Ever since the Japanese government enforced Okinawa to be part of its prefecture in 1872, all the islanders had to speak standardized Japanese as the official language.

There was a time in Okinawa when the same surname was pronounced “Higanuma.” During my childhood, I was more accustomed to calling the Naha Master, Kanryo Higanuma. Neverthless, “Higaonna” was the commonly accepted pronunciation for that surname after his death in 1915. During his time everyone called him “Higanuma.”

Kanryo Higaonna was born March 3, 1853 during the time when Okinawa Island was occupied by the Satsuma Clan of Japan. According to the recent study of Iken Tokashiki, President of Okinawa Goju Ryu Tomarite Karate-Do Kyokai, Kanryo Higaonna was born at Nishimura of Naha City as the fourth son of Kanryo Higaonna, the 10th generation of Higaonna family in Haru, lineage.

Kanryo Higaonna visited Fuchou, China, around 1877 for three years. There is an another account in regards to his visit to the city. It is said that he visited the port city in 1873 for fifteen years. Some Martial Arts historians explain his motives of visiting the city was to study the Chinese Martial Arts. Higaonna did, in fact, study a Southern Shaolin Chun style, during his stay in that city. However, his initial reason for visiting China was explained by other historians that it was the result of his political involvements.

In 1868, Japan experienced a major reformation in its history when the Shogun, Tokugawa was over turned by the liberal clans of Emperor Meiji. During the Tokugawa Shogunate era, Okinawa was part of the Satsuma Clan, the south end clan of Japan while the island also maintained their administrative connection with the Chinese government.

The Meiji Reformation brought Japan nationalism. The Meiji government wanted Okinawa as its sole affiliation and wanted the island to discontinue its trade with China. Okinawa, at this time, was divided into two political factions one was pro-Japan and the other was pro-China.

One close associate of Kanryo Higaonna was Lord Yoshimura, who had an enterprising trade of tea between the city Fuchou and Okinawa. He was a prominent pro-China activist who tried to block the Japanese settlement in Okinawa. According to historians, Higaonna carried a letter of referral for Lord Yoshimura for his trip. Higaonna never explained to anyone about the letter and stowed away with a few companions for China. In the city of Fuchou, there was a consulate of Okinawa called Ryukyu Kan. Apparently, the Ryukyu Kan represented an Okinawan petition then to the Chinese Government requesting its international pressure against the Japanese occupation of Okinawa. One possibility was that Higaonna was a chosen messenger by the pro-China Okinawa for updating others of the situation on the island.

In 1879, two years after Higaonna’s departure, Okinawa was officially ordered by the Japanese government to become its prefecture with presence of an army of Japanese police and officials. It was an extremely intense period of time for Okinawans so that earlier assumptions that Higaonna left for China for the purpose of inquiring study of Karate was unlikely.

It was said that Higaonna stayed in China for three years. During his stay, he supported himself by making and selling bamboo wares. Also, he had an opportunity to study some of the Chinese Martial Arts in the city. According to Reikichi Ohya, Higaonna was one of those who studied from a Chinese named Wei Shinzan. Wei was the student of Leu Luko who also taught Higaona so-called Fukien Crane Chang. Fukien Crane was a combined school with White Crane of South Shaolin Chang and Four Ancestor Chang.

In China, there were two counter parted arts of Chang, or fist. One is categorized as hard style, or External style. The other is Soft style or Internal style. Hard and External style represent Zen Buddhist initiated school such as various branches of Shao-lin Chun, and Soft and Internal style represent Yee Chuen, Pai Kua Chang, and Tai Chi Chuen.

The Chinese system of fist that Kanryo Higaonna studied from Wei Shinzan and Leu Luko was also known by its name Pan Gainoon, which literally means, “one half is hard and other half is soft”. Those kata practiced in the current Goju-Ryu school like Sanchin, Sanseiru, and Pecchurin all originated from that style.

Prior to visiting China, Higaonna studied Naha-te from Seiso Aragaki, (1840-1920) of Kume. Aragaki was well known among Okinawans with his favorite Kata called Seisan. Unlike Shuri-te, Naha-te represents newly inported Chinese forms from Fukien Province of China. After his return from China, Higaonna systemized the Naha-te with contemporary Chinese art, thus it was called To-te (Tode), or Chinese Hand.

Seisho Aragaki

He was born in the village of Kume Mura. He became a translator for the Chinese and translated the Okinawan language. He became know as the Cat or Maya and was known for his jumps that were soft as a cat.

Aragaki had several nicknames, including Aragaki Maya (Aragaki the cat), which is his most common name in Okinawa, even today. He was also known by the name Aragaki Kamadeunchu (“kama-de” means “sickle hands” and “unchu” was the name of a kata he was famous for, sometimes called Unsu or Unshu today).

Aragaki held the title of “Chikudon Peichin”, a title conferred upon commoners who were officials of the royal court in Okinawa, similar to a Samurai rank in Japan. He was fluent in Chinese and acted as an interpreter for the court. He was even petitioned to travel to China for his interpretive duties; there is a record of him being petitioned to go to Beijing in September of 1870. This interrupted his instruction of a young Higaonna Kanryo, himself becoming very famous for Tote instruction some years later.

It is well known that Aragaki was highly sought after for Tote instruction near the end of his life, and was definitely one of the primary Tote instructors of the 19th century. Some of his other students included Master Higaonna Kanryo (mentioned above and teacher to Master Miyagi Chojun, the Goju-Ryu founder), Master Funakoshi Gichin (Shotokan founder), Master Mabuni Kenwa (Shito-Ryu founder) and Master Uechi Kanbum (Uechi-Ryu founder). These renowned karateka sought Aragaki for training, though none of them regarded him as their primary teacher.

Aragaki’s Tote was developed from teachings of Chinese martial arts masters. It’s unknown exactly what school of gungfu he trained in, but historians generally say that he probably trained and taught Monk Fist gungfu (Arhat Boxing). The only Chinese master mentioned in association with Aragaki is someone by the name of Wai Xinxian (or Wai Shinzan), a famous gungfu master in Fuzhou, a city in Fukien province, China, although there were probably others.

Not only was he a renowned Tote expert, but Aragaki was also a superb weapons master, leaving behind several Bo and sai kata including Aragaki-no-kun, Aragaki-no-sai and Sesoku-no-kun, which has about 200 techniques, used against the sword. Aragaki’s weapons katas are thought to be long and beautiful.

Aragaki has many family members still practicing karate in Okinawa today, but his descendants are primarily associated with Goju-Ryu, a style with roots similar to Aragaki’s Tote. Despite his fame as a Tote master, and his many descendants, Aragaki left no style behind. All that remains of this famous master’s legacy are techniques and kata scattered throughout a number of modern karate and kobujutsu styles.

Very little documentation about Tote has been preserved from the 19th century, but there is one written record (a program schedule) of Aragaki Seisho performing weapons and Tote demonstrations for a Chinese ambassador to Okinawa in Shuri City (Okinawan Capital) on March 24th, 1867. Aragaki demonstrated weapons, pre-arranged sparring and the kata Seisan. This says a lot for Aragaki’s stature as a Tote master, as this was an age of Tote giants. Itosu Anko, Azato Anko and the most famous Tote master of all time, “Bushi” Matsumura were all active and very well known, yet, for whatever reasons, it was Aragaki Seisho performing a Tote demonstration for an important foreign guest.